PROTECT YOUR HOME FROM WILDFIRE

Don’t cut down — aka, “thin” — forests.

Make your house “ignition resistant.”

Although it may seem counter-intuitive, the best way to protect your home from wildfire isn’t by cutting down nearby trees or leveling every forest around.

Nor will “thinning” forests — which is cutting down 20-70% of the trees in a forest — beyond 50-100 ft. from your house offer much protection. Logging forests — sold to the public with euphemisms like, “vegetation management,” “forest treatments” and “thinning” — only dries out forests, thus increasing the likelihood of wildfire ignition. And increasing wind speeds, which fuel and intensity typically wind-driven wildland fires.

Instead, protect your home from the house-outward, not the forest-inward. Relatively simple preparations — much less expensive than regularly cutting down forests and the brush that deforesations generate — can dramatically increase the chances your house will survive a wildland fire. Examine the photo below:

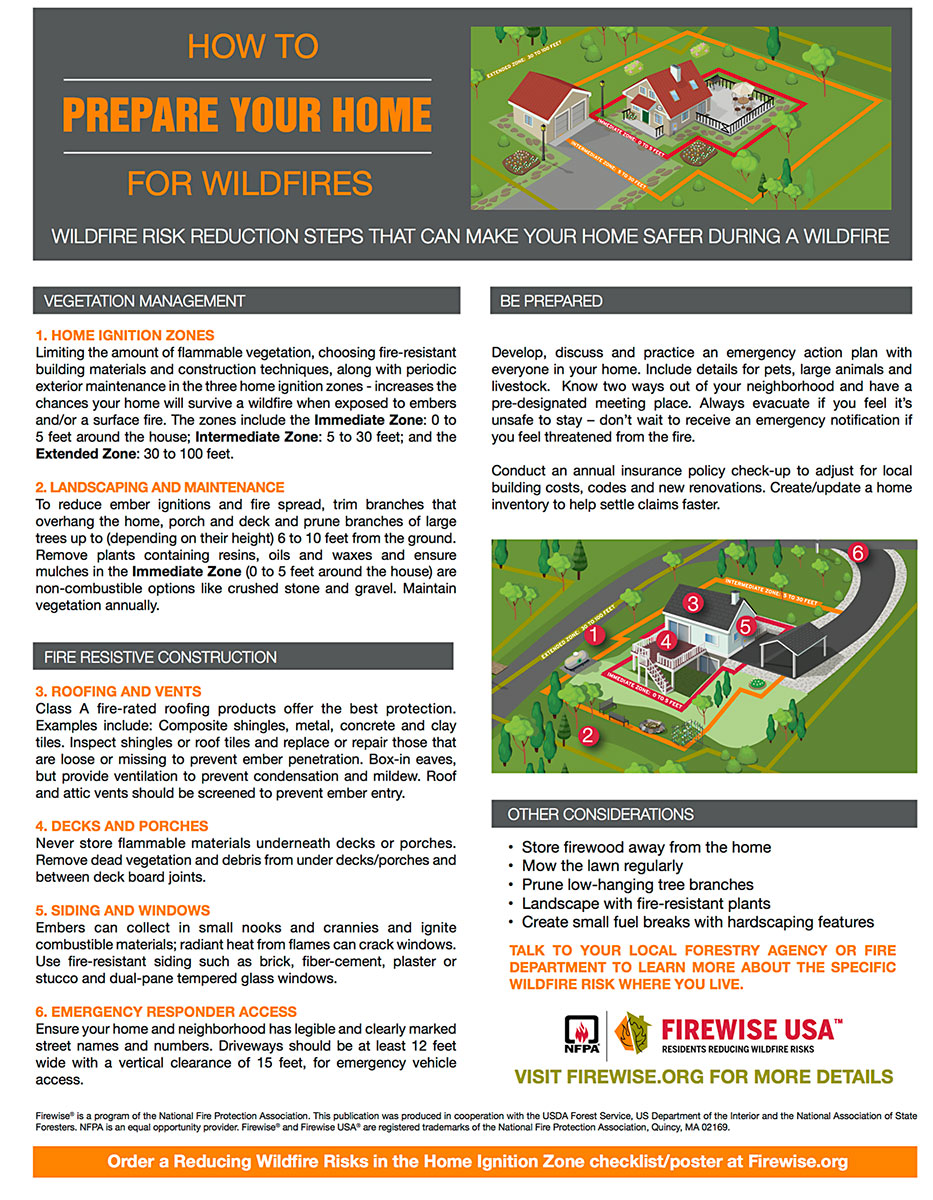

Most houses catch fire from showers of embers, called “firebrands” in the wildfire biz, which land on or near your house and cause ignitions, not from contact with direct flames.

The many resources and house treatments on this page have been proven effective. They are recommended by federal, state and county fire agencies. They are the result of decades of extensive wildfire research by scientists like Jack Cohen, Ph.D. of the U.S. Forest Service, below.

VIDEO: fire scientist Jack Cohen, Ph.D., explains how to make your house much safer in a wildfire.

Cohen has a decades-long career with the US Forest Service. If you live in a dryer region of the U.S. — like California, Arizona, Nevada — you are at greater risk from wildfire due to our heating (and thus drying) climate.

Make your house “Ignition Resistant”:

• FIRE SAFE MARIN: Home “Hardening” & Defensible Space

Simple, relatively inexpensive preparations can dramatically decrease the chances your house and nearby structures will ignite in a wildfire.

Simple, relatively inexpensive preparations can dramatically decrease the chances your house and nearby structures will ignite in a wildfire.

Defensible Space – A 2-prong approach, both “fire-hardening” your home and preparing good Defensible Space, provides the greatest level of protection. Preparing and maintaining adequate Defensible Space guards against flame contact and radiant exposures from nearby burning vegetation.

The “Home Ignition Zone” (HIZ) is the area approximately 100 feet around a house, including the house itself, where Defensible Space work should be done.

VIDEO: Defensible Space & the Zero Zone –

Fire Safe Marin shows how to protect your home from wildfire, from the house-out. (Not the forest-in).

Vents on houses can allow flying embers (aka, firebrands) to enter and ignite combustible materials in the attic, and burn a house from the inside out. Special vents have been designed to resist the intrusion of embers and flame, are commercially available, and are recommended for new houses, and to retrofit existing vent openings.

Eaves are located at the down-slope edge of a sloped roof. They serve as the transition between the roof and fascia/wall. The underside of this overhang, when given a finished appearance, is known as the soffit. Eaves and soffits are vulnerable to damage from wildfires.

Gutters – Combustible debris such as leaves and pine needles often accumulate in gutters. If ignited, combustible debris in the gutter can ignite the edge of the roof covering. Depending on the condition of the wood and presence (or absence) of metal flashing at the edge of the roof, gutter debris can allow fire to enter the attic.

Roofs & Chimneys – untreated wood shake or shingle roof coverings are the greatest threat to houses. Wind-blown debris will accumulate on roofs and in gutters. Dry debris can be ignited by wind-blown embers. You should routinely, regularly, remove vegetative debris from your roof and gutters. Chimneys require a spark arrestor screen with openings no smaller than 3/8” and no larger than 1/2”

Siding – With proper selection and maintenance of near-house vegetation, most siding materials resist typical wildfire exposures. In most cases it is less important from a wildfire exposure perspective compared with other components and assemblies.

Sprinkler systems can protect a home against the 3 basic wildfire exposures: wind-blown embers, radiant heat, and direct flame contact. Given the potential issues regarding performance, it’s recommended that use be a supplement to, and not a replacement for, already proven mitigation strategies

Decks’ vulnerability to wildfire will depend on the decking board material, any combustible materials stored under the deck or kept on the deck, and the topography and amount and condition of vegetation leading to the deck.

Fencing – The Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) recommend non-combustible fencing products when placed within five feet of a building. Using non-combustible fencing where it attaches to the building reduces the opportunity of a burning fence igniting the exterior of the structure.

LEARN MORE: https://firesafemarin.org/harden-your-home/

• NFPA Firewise USA® — “Preparing homes for wildfire”

What are the primary threats to homes during a wildfire?

Research about home destruction vs. home survival in wildfires indicates embers and small flames are the primary way the majority of homes ignite in a wildfire. Embers are burning pieces of airborne wood and/or vegetation that can be carried over a mile by the wind. They cause spot fires and ignite homes, debris and other objects.

Homeowners can use simple methods to prepare their homes to withstand ember attacks and minimize the likelihood of flames or surface fire touching the home or any attachments. Experiments, models and post-fire studies have shown homes ignite due to the condition of the home and everything around it, up to 200’ from the foundation. This is called the Home Ignition Zone (HIZ).

Watch the U.S. Forest Service VIDEO featuring fire scientist Jack Cohen, Ph.D., above.

LEARN MORE: https://www.nfpa.org/Public-Education/Fire-causes-and-risks/Wildfire/Preparing-homes-for-wildfire

The forest-altering approach has failed to keep the public safe. Instead, it mainly produces stumps, depleted budgets, and excuses. After each failure, logging proponents conveniently claim that things will be different if they get more money for more cutting. Yet, we now see the fires burning readily in places where they have already done lots of cutting. In fact, some of the fastest and most intense fire spread is occurring in these cut areas (see pg. 12).

Beyond being ineffective and even counterproductive, the forest-altering approach puts more carbon into the atmosphere (see pgs. 13-15) and more pollution in vulnerable communities (see pg. 15).

And perhaps the biggest harm from the forest-altering approach is that it diverts attention and resources away from real solutions, such as fire-safety home retrofits that genuinely protect communities during inevitable wildfires.

VIDEO: “The Fire Paradox”: “The more we try to remove fire, the worse we make it.” – With Mark Finny & Jack Cohen, research forester with the U.S. Forest Service.

Wildfire is a powerful, necessary and, unavoidable component of a healthy, natural forest ecosystem. We have a complex relationship with this force of nature, especially now with wildland fires near houses, towns and cities that have encroached on dwindling forests and open space.