The essay below, by Rick Halsey, Director of the California Chaparral Institute of San Diego County, CA is an excerpt of a letter to the California Coastal Commission, reprinted with permission from the author. Bolding added by TreeSpirit Project.

The forest destruction project @ Tomales Bay State Park:

The forest destruction project @ Tomales Bay State Park:

GUEST ESSAY by:

Rick Halsey, Director

The California Chaparral Institute

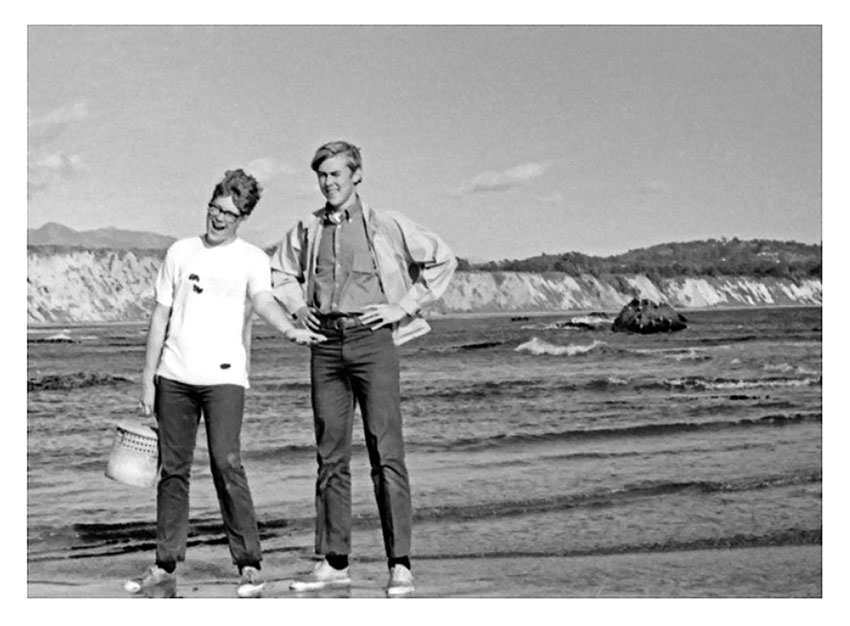

The author, Rick Halsey, above (right), with friend Eric Strom, 1970; the summer they canvassed for CA Prop 20 to create the California Coastal Commission.

The forest destruction project @ Tomales Bay State Park

(aka, “Forest Health & Wildfire Resilience” PWP, Public Works Plan)

By Rick Halsey, March 26, 2024

As I reflect on my decades-long effort to protect Nature from misconceptions and vested interests determined to demonize vibrant ecosystems, it is bittersweet to be writing this letter. It has been difficult to see the California Coastal Commission, under pressure from Cal Fire, helping to facilitate the loss of the very coastal habitats it was originally chartered to protect.

On July 8, 2021, we [California Chaparral Institute] offered a well-documented comment letter and oral testimony to the Commission that pointed out major errors in staff reports that supported two large PWP habitat clearance plans along the coast of San Mateo and Santa Cruz Counties – plans similar to the Tomales Bay State Park PWP.

Like the Tomales Bay PWP [Public Works Project], these plans repeated the persistent misconception about past fire suppression, claiming that natural habitat nearly everywhere is an unnaturally dense, unsightly mess growing out of control, and that humans know best – all antagonistic reflections emerging from the shift away from embracing Nature’s intrinsic value, toward human-centrism.

The recommended solution of the latest PWP is also the same: habitats need to be cleared, mowed, logged, and/or sprayed with herbicide to remove the offending native plant growth – all described with Orwellian acuity as improving forest or ecological health and resiliency.

The actual purpose is to prevent what humans have erroneously defined as “bad” high-intensity fire in favor of “good” low intensity fire. This, despite the fact that high-intensity fire is the natural condition for many ecosystems, including the Bishop pine being targeted by the [Tomales Bay State Park forest] PWP. Indeed, all ecosystems are naturally subject to high-intensity fire when the conditions line up, conditions that have always determined the size and intensity of wildfires: long-term drought, low humidity, high temperatures, and wind.

The fundamental problem is that the binary “bad” vs. “good” view of fire is an artificial construct reflecting the fear humans have of fire and their dislike of burned trees and blackened ground. It has nothing to do with natural ecosystem function.

During the 2021 public testimony, ten out of eleven speakers spoke against the two plans before the Coastal Commission. Most pointed out that the underlying reports had misrepresented the region’s fire regimes to justify the plans’ approach, as does the Tomales Bay PWP.

The commission’s response? Not one commissioner asked a single question of staff or the agencies supporting the plans to reflect as to why so many science-based public comments contradicted the main assumptions underlying the plans. After several commissioners repeated the exact same misconceptions about fire suppression that had been corrected earlier by the testimony, the Commission voted unanimously to approve the plans.

It is a behavior we have come to expect – commissioners, politicians, and board members typically endure, rather than embrace, public testimony. Decisions are typically made long before the hearing begins.

The Return of Human-centrism

Where once wildness was seen as sublime, manifesting the beautifulness of life, allowing us to connect to our ancestral selves and find inspiration in the untrammeled, natural world, it is becoming, as it was prior to the environmental movement, a commodity that needs to serve us. To repackage this shift in thinking and accommodate the still influential biocentric perspective, purveyors of Nature exploitation have been successful in convincing much of the public into believing not only that Nature serves us, but that it can’t survive without our tending, our gardening.

During public presentations concerning the PWP, Tomales Bay State Park officials blame human activity (colonialism, fire suppression, cessation of Native American fire use, etc.) for the current condition of the Bishop pine forests on the Pt. Reyes Peninsula. In short, the forests have become unhealthy because they have not been tended properly by humans – the common rationale to support logging and habitat clearance operations throughout California.

Foundational to this rationale is the false notion that to function properly, Nature needs human beings.

This increasingly popular human-centric model is exemplified by One Tam, a habitat clearance advocacy group that focuses on the wildlands of nearby Mt. Tamalpais:

[EDITOR’S NOTE: The italicized quotation below is a false narrative advanced, here, by One Tam, and by many others elsewhere.]

“But left to themselves, forests can also grow large and dense, putting the entire system in danger of catastrophic wildfire, loss of life and livelihoods, and extreme carbon emissions.

These forests need care, and Tribal stewardship responsibilities to gather, hunt, fish, burn, and tend in coordination with management rooted in the best available science will continue to improve and maintain these ecosystems into the future.”

In other words, creating Nature in our own image, as a garden – for humans, by humans.

The fact that forests and native shrublands thrived for millions of years prior to the arrival of Homo sapiens in North America is ignored.

As evidenced by the on-going ecological disaster caused by the clearance of post-fire habitat in Cuyamaca Rancho State Park in San Diego County, a human-centric approach is contrary to the California State Parks’ mission “to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological diversity.” Because conifers are preferred over naturally regenerating, shrubland communities, large areas of Cuyamaca Rancho State Park have been masticated, burned, and sprayed with herbicide to rid the landscape of extremely biodiverse successional habitat.

Exploitation of Native American Culture

To further legitimize the anthropocentric paradigm, land management agencies, logging and biomass interests, and many environmental groups have appropriated Native American cultural burning practices.

The strategy is an old one for conquering societies – exploiting the conquered in pursuit of self-interest and financial gain, in this case millions of dollars in grants to fund non- profits, government agencies, and private contractors.

The appeal is easy to understand. The grantor provides money to organizations to fund their administrative salaries if the organization agrees the clear or burn habitat. The pressure on regulatory agencies to approve projects with money waiting in the wings can be enormous, regardless of the negative environmental impacts, especially when the projects provide opportunities for performative allyship – habitat clearance in the name of Indigenous Peoples.

Native Americans long used cultural burning practices near their population centers for food- and fiber-related purposes, particularly at low elevations. These fires were purposeful and localized and may have created vegetation mosaics consisting of shrublands, woodlands, and grasslands near villages. Localized conversion of habitats by Native Americans in these areas would have resulted in a shift from dense shrublands and/or forests to a different assemblage favoring native herbaceous plants.

However, natural habitats across the broader California landscape remained relatively undisturbed, being shaped by the same physical, ecological, and evolutionary processes that have occurred for millions of years – to claim otherwise is contrary to science and logic.

Equating the mechanized clearance of large swaths of habitat with chain saws, grinding machines, drip torches, and chemicals to the tending of localized areas that Indigenous Peoples conducted to sustain their cultures is an affront to the respect and intimate connections many Native American cultures hold for Nature.

Invoking Indigenous fire use to justify habitat clearance plans also ignores the fact that the manipulation of the environment by humans has been for the purpose of improving human survival, to change wild into something less so.

As evidenced by the drastic changes many early inhabitants caused to the environments in which they occupied, from extinctions to the loss of native shrublands and forests, efforts to restore wild landscapes need to focus on what may have been prior to the arrival of humans, if restoration of native habitat is the actual objective.

Nature Seen As Fuel Rather Than a Source of Life

Nature is increasingly being viewed as something broken, in need of fixing. This is exemplified in the Tomales Bay PWP and State Park presentations.

The rationale given for this view is that Nature is overgrown, clogged with too many trees, too many shrubs. Regardless of ecosystem type, the claimed cause for the mess is fire suppression.

The prescription involves the removal of Nature through clearance, euphemistically referred to as “restoration.”

To promote the preferred “treatment,” legions of land managers, fire managers, and environmental consultants have successfully convinced much of the public that wild Nature is ugly, “unnatural.” We are told that lush, dense forests, piles of downed wood and leaf litter filled with rich fungal networks, and standing dead trees used by cavity nesting birds and an array of insects are not beautiful habitats, but rather “unnatural accumulations” of native vegetation in need of removal.

In the case of the Bishop pine forests in Tomales Bay State Park, naturally dense, even-aged wild landscapes shall become instead, pastoral, Disneyland-like mosaics of mixed-aged greenery to create a more pleasing setting to suit human sensibilities. The stated goal is to prevent the very kind of fire that the Bishop pine species has evolved to survive. Never mind that:

- the Bishop pine fire regime is defined by infrequent, high-intensity fire that creates large stands of even-aged forest;

- old-growth Bishop pine forests are naturally characterized by large numbers of dead trees, piles of downed wood, thick layers of litter, and dense shrub growth;

- and combined with a moist climate and one of the lowest lightning frequencies in North America, Point Reyes Peninsula plant communities have natural fire return intervals of a century or more.

The larger tragedy —once Park managers conduct their initial habitat clearance operations — is that future management will continue to be based on unscientific, subjective metrics within the Cal Fire Vegetation Treatment Program (VTP). The VTP claims that after 40 years, Bishop pines are ready to be “treated” again because they will be “outside of their natural fire regime.” In fact, at 40 years, Bishop pine forests are just entering their mid-seral stage when the forest is yet to reach its natural, old-growth climax stage.

And as with all the other prescriptions in the VTP, managers can always burn or masticate the forest prior to 40 years if they deem it contains “uncharacteristic fuel loads,” i.e., native habitat. Such a determination will not be subject to independent oversight as the VTP is a “programmatic” document, meaning the usual opportunities for the public to review projects as provided by the California Environmental Quality Act will not be available.

The 40-year metric dictated by the Cal Fire VTP is based on the CNPS Manual on California Vegetation. The only reference the Manual uses to support the 40-year number is a four-decade old, non-peer reviewed Master’s thesis that is not readily available (Sugnet 1985). This is a typical problem for the CNPS Manual as many of the fire regime intervals listed in the document are guesses, not based on solid research.

In fact, recent papers indicate that the natural fire return interval for Bishop pine communities is extremely difficult to determine. However, what we do know is that natural moisture levels and low lightning frequency in the Point Reyes area, coupled with historical data, indicate natural fire frequency in Tomales State Park is one of the lowest in North America – the opposite to what the manual and the VTP indicate.

Consequently, the primary basis for the Tomales Bay State Park PWP, that the region suffers from not enough fire, is not supported by the science.

For the record

…our letter from 2021… addresses the same issues that plague the current Tomales Bay State Park PWP [Public Works Project]. Merely replace the terms “chaparral” or “redwood forest” in the letter with “Marin [County] manzanita” and “Bishop pine” – the same basic misconceptions are addressed, just the names have changed.

Our effort to help Cal Fire develop a rational, science-based fire risk reduction plan (VTP) began in 2005. We were on the cusp of producing such a plan until the incoming Newsom administration rejected years of work and engaged Ascent Environmental to produce a Programmatic EIR that allows Cal Fire and its partners (e.g. agencies, non-profits) to obtain millions of dollars to clear habitat across hundreds of thousands of acres without objective oversight or citizen involvement.

We filed a lawsuit in 2020 to stop the environmental damage the VTP would cause. Our case is currently on appeal.

• 5 Reasons We Challenged the VTP in Court can be found here: https://chaparralwisdom.org/2020/03/02/five-reasons-we-are-taking-cal-fire-to-court/

• The 15-year history of the effort to bring science into the Cal Fire VTP [is] here:

https://californiachaparral.org/threats/cal-fire

Despite past actions by the Coastal Commission, we still hold out hope that this time [April 2024] the Commissioners will find the courage to be skeptical, question assumptions, reject the Tomales Bay PWP, and inform State Parks they need to put Nature first.

For Nature,

Richard W. Halsey, Director

Richard W. Halsey, Director

The California Chaparral Institute

https://californiachaparral.org

TreeSpirit ADDENDUM:

We are grateful to Rick Halsey and The California Chaparral Institute for permission to reprint this essay, and for all the Institutes work to educate the public and challenge the industrial “management” (aka, destruction) of California’s quickly vanishing wildlands.

Disturbingly, Coastal Commissioners approved the Tomales Bay deforestation project unanimously (4,11,24), quickly, without debate, nor any discussion or engagement with (over 20) citizens and scientists who overwhelmingly spoke against the project at the public hearing.

No questions were asked, nor was there any discussion regarding the content of the 300 pages of practical, wildfire, and scientific challenges submitted by the public to the Commission.]

READ MORE about the Tomales Bay deforestation project:

• TreeSpirit’s Tomales Bay deforestation webpage: http://www.TreeSpiritProject.com/CalFire

• Essay, “Orwell’s Forest” : https://treespiritproject.com/deforestation/orwells-forest/